Section contents

| Python objects: |

|

|---|---|

| Numpy provides: |

|

>>> import numpy as np

>>> a = np.array([0, 1, 2, 3])

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3])

Tip

For example, An array containing:

Why it is useful: Memory-efficient container that provides fast numerical operations.

In [1]: L = range(1000)

In [2]: %timeit [i**2 for i in L]

1000 loops, best of 3: 403 us per loop

In [3]: a = np.arange(1000)

In [4]: %timeit a**2

100000 loops, best of 3: 12.7 us per loop

On the web: http://docs.scipy.org/

Interactive help:

In [5]: np.array?

String Form:<built-in function array>

Docstring:

array(object, dtype=None, copy=True, order=None, subok=False, ndmin=0, ...

Looking for something:

>>> np.lookfor('create array')

Search results for 'create array'

---------------------------------

numpy.array

Create an array.

numpy.memmap

Create a memory-map to an array stored in a *binary* file on disk.

In [6]: np.con*?

np.concatenate

np.conj

np.conjugate

np.convolve

The recommended convention to import numpy is:

>>> import numpy as np

1-D:

>>> a = np.array([0, 1, 2, 3])

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3])

>>> a.ndim

1

>>> a.shape

(4,)

>>> len(a)

4

2-D, 3-D, ...:

>>> b = np.array([[0, 1, 2], [3, 4, 5]]) # 2 x 3 array

>>> b

array([[0, 1, 2],

[3, 4, 5]])

>>> b.ndim

2

>>> b.shape

(2, 3)

>>> len(b) # returns the size of the first dimension

2

>>> c = np.array([[[1], [2]], [[3], [4]]])

>>> c

array([[[1],

[2]],

[[3],

[4]]])

>>> c.shape

(2, 2, 1)

Exercise: Simple arrays

Tip

In practice, we rarely enter items one by one...

Evenly spaced:

>>> a = np.arange(10) # 0 .. n-1 (!)

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

>>> b = np.arange(1, 9, 2) # start, end (exclusive), step

>>> b

array([1, 3, 5, 7])

or by number of points:

>>> c = np.linspace(0, 1, 6) # start, end, num-points

>>> c

array([ 0. , 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1. ])

>>> d = np.linspace(0, 1, 5, endpoint=False)

>>> d

array([ 0. , 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8])

Common arrays:

>>> a = np.ones((3, 3)) # reminder: (3, 3) is a tuple

>>> a

array([[ 1., 1., 1.],

[ 1., 1., 1.],

[ 1., 1., 1.]])

>>> b = np.zeros((2, 2))

>>> b

array([[ 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0.]])

>>> c = np.eye(3)

>>> c

array([[ 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 1.]])

>>> d = np.diag(np.array([1, 2, 3, 4]))

>>> d

array([[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 2, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 3, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 4]])

np.random: random numbers (Mersenne Twister PRNG):

>>> a = np.random.rand(4) # uniform in [0, 1]

>>> a

array([ 0.95799151, 0.14222247, 0.08777354, 0.51887998])

>>> b = np.random.randn(4) # Gaussian

>>> b

array([ 0.37544699, -0.11425369, -0.47616538, 1.79664113])

>>> np.random.seed(1234) # Setting the random seed

Exercise: Creating arrays using functions

You may have noticed that, in some instances, array elements are displayed with a trailing dot (e.g. 2. vs 2). This is due to a difference in the data-type used:

>>> a = np.array([1, 2, 3])

>>> a.dtype

dtype('int64')

>>> b = np.array([1., 2., 3.])

>>> b.dtype

dtype('float64')

Tip

Different data-types allow us to store data more compactly in memory, but most of the time we simply work with floating point numbers. Note that, in the example above, NumPy auto-detects the data-type from the input.

You can explicitly specify which data-type you want:

>>> c = np.array([1, 2, 3], dtype=float)

>>> c.dtype

dtype('float64')

The default data type is floating point:

>>> a = np.ones((3, 3))

>>> a.dtype

dtype('float64')

There are also other types:

| Complex: | >>> d = np.array([1+2j, 3+4j, 5+6*1j])

>>> d.dtype

dtype('complex128')

|

|---|---|

| Bool: | >>> e = np.array([True, False, False, True])

>>> e.dtype

dtype('bool')

|

| Strings: | >>> f = np.array(['Bonjour', 'Hello', 'Hallo',])

>>> f.dtype # <--- strings containing max. 7 letters

dtype('S7')

|

| Much more: |

|

Now that we have our first data arrays, we are going to visualize them.

Start by launching IPython:

$ ipython

Or the notebook:

$ ipython notebook

Once IPython has started, enable interactive plots:

>>> %matplotlib

Or, from the notebook, enable plots in the notebook:

>>> %matplotlib inline

The inline is important for the notebook, so that plots are displayed in the notebook and not in a new window.

Matplotlib is a 2D plotting package. We can import its functions as below:

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # the tidy way

And then use (note that you have to use show explicitly if you have not enabled interactive plots with %matplotlib):

>>> plt.plot(x, y) # line plot

>>> plt.show() # <-- shows the plot (not needed with interactive plots)

Or, if you have enabled interactive plots with %matplotlib:

>>> plot(x, y) # line plot

1D plotting:

>>> x = np.linspace(0, 3, 20)

>>> y = np.linspace(0, 9, 20)

>>> plt.plot(x, y) # line plot

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at ...>]

>>> plt.plot(x, y, 'o') # dot plot

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at ...>]

[source code, hires.png, pdf]

2D arrays (such as images):

>>> image = np.random.rand(30, 30)

>>> plt.imshow(image, cmap=plt.cm.hot)

>>> plt.colorbar()

<matplotlib.colorbar.Colorbar instance at ...>

[source code, hires.png, pdf]

See also

More in the: matplotlib chapter

Exercise: Simple visualizations

The items of an array can be accessed and assigned to the same way as other Python sequences (e.g. lists):

>>> a = np.arange(10)

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

>>> a[0], a[2], a[-1]

(0, 2, 9)

Warning

Indices begin at 0, like other Python sequences (and C/C++). In contrast, in Fortran or Matlab, indices begin at 1.

The usual python idiom for reversing a sequence is supported:

>>> a[::-1]

array([9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0])

For multidimensional arrays, indexes are tuples of integers:

>>> a = np.diag(np.arange(3))

>>> a

array([[0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 2]])

>>> a[1, 1]

1

>>> a[2, 1] = 10 # third line, second column

>>> a

array([[ 0, 0, 0],

[ 0, 1, 0],

[ 0, 10, 2]])

>>> a[1]

array([0, 1, 0])

Note

Slicing: Arrays, like other Python sequences can also be sliced:

>>> a = np.arange(10)

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

>>> a[2:9:3] # [start:end:step]

array([2, 5, 8])

Note that the last index is not included! :

>>> a[:4]

array([0, 1, 2, 3])

All three slice components are not required: by default, start is 0, end is the last and step is 1:

>>> a[1:3]

array([1, 2])

>>> a[::2]

array([0, 2, 4, 6, 8])

>>> a[3:]

array([3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

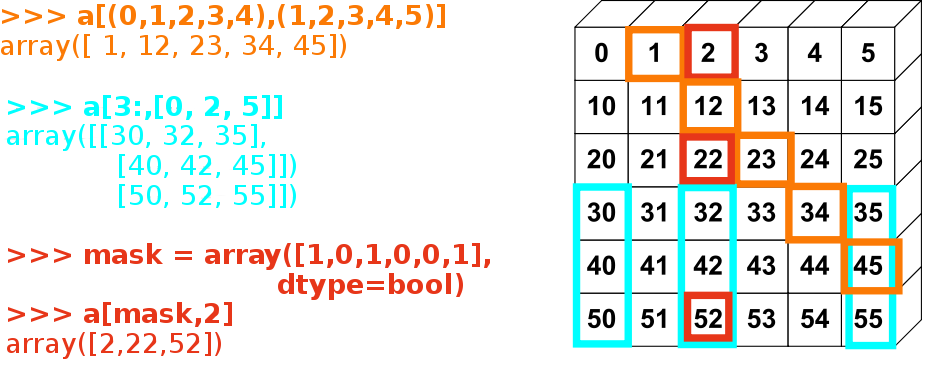

A small illustrated summary of Numpy indexing and slicing...

You can also combine assignment and slicing:

>>> a = np.arange(10)

>>> a[5:] = 10

>>> a

array([ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10])

>>> b = np.arange(5)

>>> a[5:] = b[::-1]

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0])

Exercise: Indexing and slicing

Try the different flavours of slicing, using start, end and step: starting from a linspace, try to obtain odd numbers counting backwards, and even numbers counting forwards.

Reproduce the slices in the diagram above. You may use the following expression to create the array:

>>> np.arange(6) + np.arange(0, 51, 10)[:, np.newaxis]

array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15],

[20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25],

[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35],

[40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45],

[50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]])

Exercise: Array creation

Create the following arrays (with correct data types):

[[1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 2],

[1, 6, 1, 1]]

[[0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[2., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 3., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 4., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 5., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 6.]]

Par on course: 3 statements for each

Hint: Individual array elements can be accessed similarly to a list, e.g. a[1] or a[1, 2].

Hint: Examine the docstring for diag.

Exercise: Tiling for array creation

Skim through the documentation for np.tile, and use this function to construct the array:

[[4, 3, 4, 3, 4, 3],

[2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1],

[4, 3, 4, 3, 4, 3],

[2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1]]

A slicing operation creates a view on the original array, which is just a way of accessing array data. Thus the original array is not copied in memory. You can use np.may_share_memory() to check if two arrays share the same memory block. Note however, that this uses heuristics and may give you false positives.

When modifying the view, the original array is modified as well:

>>> a = np.arange(10)

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

>>> b = a[::2]

>>> b

array([0, 2, 4, 6, 8])

>>> np.may_share_memory(a, b)

True

>>> b[0] = 12

>>> b

array([12, 2, 4, 6, 8])

>>> a # (!)

array([12, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

>>> a = np.arange(10)

>>> c = a[::2].copy() # force a copy

>>> c[0] = 12

>>> a

array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

>>> np.may_share_memory(a, c)

False

This behavior can be surprising at first sight... but it allows to save both memory and time.

Worked example: Prime number sieve

Compute prime numbers in 0–99, with a sieve

>>> is_prime = np.ones((100,), dtype=bool)

>>> is_prime[:2] = 0

>>> N_max = int(np.sqrt(len(is_prime)))

>>> for j in range(2, N_max):

... is_prime[2*j::j] = False

Skim through help(np.nonzero), and print the prime numbers

Follow-up:

- Skip j which are already known to not be primes

- The first number to cross out is

Tip

Numpy arrays can be indexed with slices, but also with boolean or integer arrays (masks). This method is called fancy indexing. It creates copies not views.

>>> np.random.seed(3)

>>> a = np.random.random_integers(0, 20, 15)

>>> a

array([10, 3, 8, 0, 19, 10, 11, 9, 10, 6, 0, 20, 12, 7, 14])

>>> (a % 3 == 0)

array([False, True, False, True, False, False, False, True, False,

True, True, False, True, False, False], dtype=bool)

>>> mask = (a % 3 == 0)

>>> extract_from_a = a[mask] # or, a[a%3==0]

>>> extract_from_a # extract a sub-array with the mask

array([ 3, 0, 9, 6, 0, 12])

Indexing with a mask can be very useful to assign a new value to a sub-array:

>>> a[a % 3 == 0] = -1

>>> a

array([10, -1, 8, -1, 19, 10, 11, -1, 10, -1, -1, 20, -1, 7, 14])

>>> a = np.arange(0, 100, 10)

>>> a

array([ 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90])

Indexing can be done with an array of integers, where the same index is repeated several time:

>>> a[[2, 3, 2, 4, 2]] # note: [2, 3, 2, 4, 2] is a Python list

array([20, 30, 20, 40, 20])

New values can be assigned with this kind of indexing:

>>> a[[9, 7]] = -100

>>> a

array([ 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, -100, 80, -100])

Tip

When a new array is created by indexing with an array of integers, the new array has the same shape than the array of integers:

>>> a = np.arange(10)

>>> idx = np.array([[3, 4], [9, 7]])

>>> idx.shape

(2, 2)

>>> a[idx]

array([[3, 4],

[9, 7]])

The image below illustrates various fancy indexing applications

Exercise: Fancy indexing